And when certain musicians refuse, Murphy allegedly responds with something along the lines of: a) "Well, he's a washed-up has been trying to maintain cred" (in the case of Slash, former guitarist of hard rock bands Guns n' Roses and Velvet Revolver); or b) "They're selfish jerks" (in the case of Nathan Followill of Kings of Leon).

In the latter case, Murphy specifically said, "F--- you, Kings of Leon. They're self-centered assholes, and they missed the big picture. They missed that a 7-year-old kid can see someone close to their age singing a Kings of Leon song, which will maybe make them want to join a glee club or pick up a musical instrument. It's like, OK, hate on arts education. You can make fun of Glee all you want, but at its heart, what we really do is turn kids on to music."

While I disagree with Followill's sexist and homophobic response to Murphy via Twitter, which read "Dear Ryan Murphy, let it go. See a therapist, get a manicure, buy a new bra. Zip your lip and focus on educating 7yr olds how to say f**k.," and which Followill later recanted, I also disagree with Murphy.

First, no band should be obligated to give their permission for a song to be used. Like Murphy, they're artists. Their major assets are the songs they've created. They should have the right to decide on which platforms and in what forms those songs appear. Considering the way the show thoughtfully addresses high school bullying, you'd think Murphy wouldn't take to verbal bullying of the artists who refuse to let their songs be used.

Why Glee is bad for fans of good music

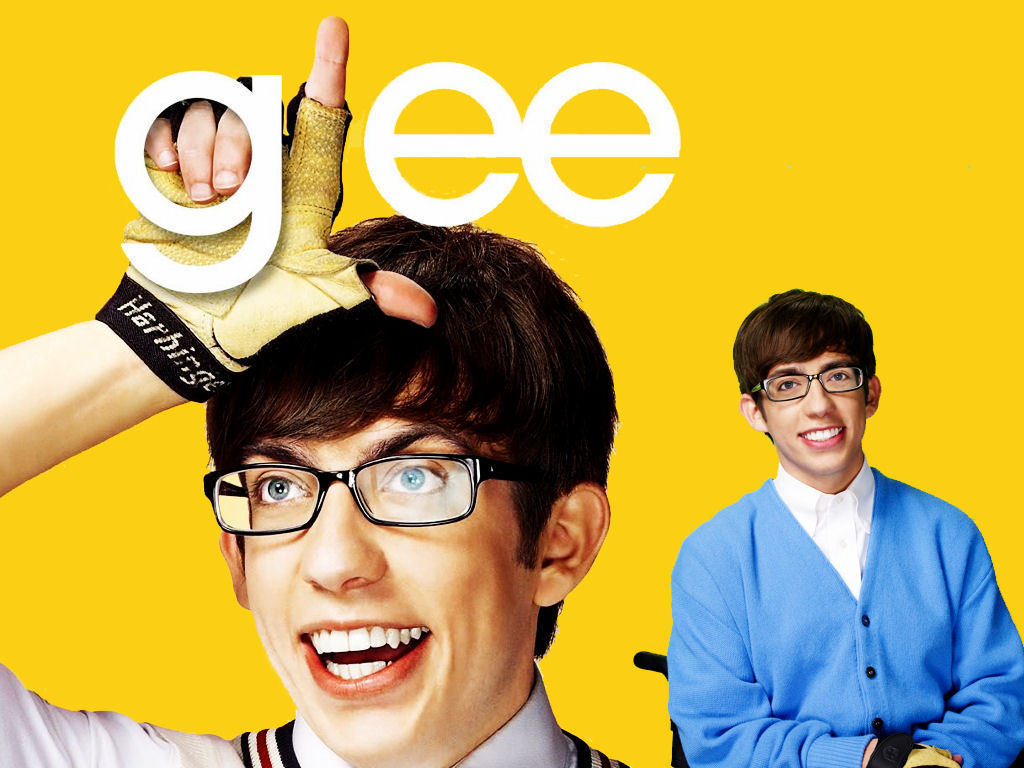

Second, Murphy's claims of "education" are somewhat dubious. I agree that the show provides a platform of visibility for people with disabilities,

|

| Keven McHale as Artie |

And the show is great because it highlights the struggle of self-identified gay and bisexual boys and girls dealing with coming out (or not) to family and friends, weight and body issues, school bullying, and alcohol abuse (albeit the last one in ways more humorous than not). But let's be clear, the show is problematic in many ways (see above clip).

However, what's emerging as the most problematic aspect of Glee is not the way, according to some, it ruins otherwise great songs that have aged well. I liked Glee's remake of "Don't Stop Believing." And while Kurt's rendition of "I Want to Hold Your Hand" was different from the original

I've found that most of their remakes are actually faithful to the original (Queen's "Fat Bottom Girls," for example).

No, what's more troubling to me is the way Glee is beginning to fit into the current musical landscape, which is littered with the deluded aspirations of would-be pop stars. For all Glee's talk about a choir being a "team" and how kids shouldn't fight over solos, that's just not the norm in the music realm anymore. Many of us have already witnessed this troubling trend of frightening and fascinating fixations of being a "star" on American Idol.

I argue that, far from Murphy's argument that Glee will make kids want to join show choirs and take music classes in high school, the popularity of Glee will instead feed into the already burgeoning narcissistic, social media-driven solo artist path many kids seem to want to take after watching Justin Bieber hit it big. And unlike Bieber, who is actually talented (and, for all I know, not narcissistic), I think Glee will give kids and their parents (particularly the parents) even more confidence that their kid can be the next "star."

Getting young people into music, really? Is this what we're talking about?

Because if it is, I'd like to see a show that discourages Rebecca Black and her parents (and folks with the same deluded aspirations as they have) from ever entering the music business.

So, Ryan Murphy, please don't give bands a hard time about not lending you their music. They may be doing us all a favor.